As it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be: [Bach] without end. Amen. Amen.

On Stage Fright

The tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction. —William Blake, from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

I would compare my experiences of stage fright to a waking nightmare— heart palpitations, tinnitus, sensitivity to light, blurred vision, flushed cheeks, cold extremities, closed throat, and lack of air in the room.

Strangely, for the last several years, my encounters with stage fright during performance have been contextual, in that there is really only one environment where I invariably struggle with nerves: church.

Some degree of performance anxiety is always given, since the performing arts is a high-risk field, where one’s professional output is presented publicly and in real time. Intellectually, I know I can assign my own stage fright as residual emotions dating back to my earliest performing experiences in childhood. Additionally, I think every musician has certain niches within their field where they shine more brightly, be it repertoire, format, environment, or style. As I seldom perform in a religious setting, there is for me little, if any, home field advantage.

I could probably leave it at that, and close with a diplomatically open-ended conclusion like: “Sacred spaces and performing rituals are designed both to inspire wonder and fear, and all that is required for an artist to transcend any inner conflict is purity of intent and a little reprogramming.” But what I have addressed so far are only the practical causes of my situational performance anxiety and not the subconscious, and I feel that any superficial understanding in addressing one and not the other, would only generate a superficial conclusion. Therefore, I am going to swim around in this a bit more.

The fool who persists in his folly will become wise. —William Blake, from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

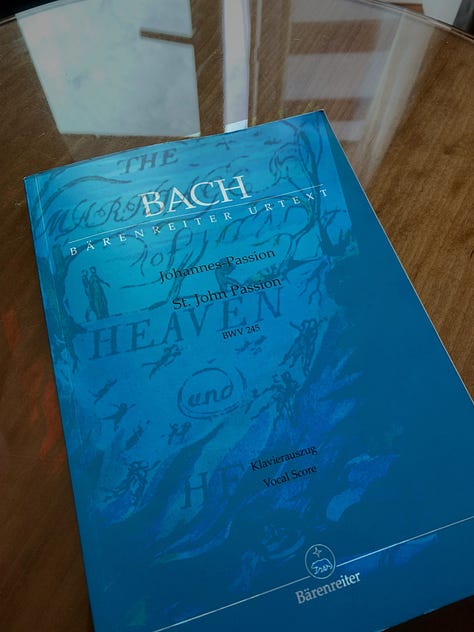

This inquisition into performance anxiety came about during two concerts in Switzerland during the Easter holiday, as the soprano soloist in Bach’s Johannespassion. I had just finished a tour of opera performances in a production that required me to simulate a sex act in a dominatrix costume. Hence, my Midwestern wallflower brain could not grasp why I was experiencing performance jitters and brain fog, rehearsing standard repertoire while fully clothed!

Growing up, I was a highly sensitive personality, who took the communication and behaviors of others very seriously1. While my religious upbringing was not so devout in comparison with the experiences of others, it was rigorous enough to observe that religious institutions used existential fears and the human need for belonging in order to impose certain belief systems and control behavior within their community. This sense of alienation and spiritual manipulation is more or less what I have attributed as the cause of any stage fright. I left religion during college, with the attitude of “You cannot drink the milk if there is even one drop of poison.”

The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom; for we never know what is enough until we know what is more than enough. —William Blake, from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

To be honest, some of the dogma and orthodoxy I take issue with in religion are also present in other identity camps2 that one might align oneself with, from political ideology and nationality, to social movements and, yes, professional communities such as classical music. To illustrate: the deification of dead composers, treating the musical score as a sacred text, glorifying tradition as the be-all and end-all of performance practice, narratives that reinforce suffering and sacrifice for the promise of enlightenment or paradise, and a sense of belonging as conditional on conforming to certain norms.

I think when one belongs to a particular social group with a shared philosophy and vision, it is understandable that the expectation is that its members uphold a certain degree of moral purity within that context, and it is in the extreme of this mentality where fundamentalism can get a bit out of hand. While I still stand by my decision to part ways with the conventional model of religion, my response today to my younger self’s drop-of-poison-in-the-milk reasoning would probably sound something like: “Yeah, well, try not to starve yourself in protest.” This all-or-nothing oversimplification of a phase in my 20s completely overlooked experiences of meaningful spirituality and authentic fellowship I’d had through participating in church choir as a kid, relationships that I still maintain today. Additionally, I must also admit that I do believe the artistic path is a spiritual path, which shares symbolism with religion, in that one can view an artist as creator, seeker, sage, visionary, alchemist, storyteller, martyr, and so on. Moreover, had I applied the same reductionist attitude with which I had decided to leave religion towards music, I know there is absolutely no way I would still be in the arts field today.

Jesus was all virtue and acted purely from impulse, not from rules. —William Blake, from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

With all this in mind, during the preparation phase of Bach’s Johannespassion, I had felt conflicted having to sing the text “Ich folge dir gleichfalls mit freudigen Schritten”, as it had reminded me of a toxic authority dynamic within the religious community that reinforced blind faith and rejected inquiry. Fortunately, my dog Bernadette accompanied me one day to the practice space, and during a break, I laughed at the thought that in my case, she quite literally had “followed with joyful steps” in exactly the same spirit as my aria. I am not saying this occurrence calmed my nerves in the moment of performance, but it had certainly been an adorable invitation to look more deeply into how my own life experiences made it difficult to approach the text, music, and setting with an open heart.

Those who restrain desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained. —William Blake, from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

How might we define fear as part of the human condition, whether within a religious or performing context: Separation? Resistance? Doubt? Respect?

And how, then, should we engage with it when we are confronted by it? Do we retreat into the perceived safety of familiarity and knowing better? Or embrace it as an opportunity for personal and collective expansion, an invitation to journey into the unknown?

I confess, I am not sure what conclusions can be drawn from this tangent of self-reflection, at least in terms of finding a more meaningful cure for performance anxiety. And at this point in time, it seems that real life is unfortunately far more terrifying than any stage, so perhaps this effort has all been for naught. If anything, when it comes to stage performance, I am comforted in the knowledge that my existential fears apparently exceed concerns over my own female vanity. I suppose since my interest lies in the emotional causes of stage fright and not the logical, a practical answer would not be what is needed here. In any case, it is not really in my nature to impart advice, neither for myself nor others.

I promise I am far more “solution oriented” when it comes to direct human-to-human communication and interaction, at least within a professional context, but arriving at a conclusion has never really been my intent with this writing space on Substack. Contraries3 such as emotion and logic, faith and reason, fear and love, innocence and experience, duality and unity; all contribute to increasing ones depth of understanding, about the nature of human existence, and about how we relate to one another, and to ourselves. Therefore, “in conclusion”, I am aspiring in the future to approach stage fright, and other experiences of fear, with enthusiasm— BOTH in the spirit of its Ancient Greek etymology (“possessed or inspired by God”) AND its post-Enlightenment rational definition (“passionate engagement”).

Eternity is in love with the productions of time. —William Blake, from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

What is the difference Between your experience of Existence And that of a saint? The saint knows That the spiritual path Is a sublime chess game with God And that the Beloved Has just made such a Fantastic Move That the saint is now continually Tripping over Joy And bursting out in Laughter And saying, "I Surrender!" Whereas, my dear, I am afraid you still think You have a thousand serious moves. Tripping Over Joy, by Hafiz, from I Heard God Laughing

Not much has changed in this respect.

More commonly referred to as “socio-cultural groups”.

FINALLY I am addressing all of these beautiful quotes I have sprinkled throughout this post from William Blake’s text The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, eh?!